What We Need to Find the Cause

We need a new way of thinking to address the rapid spread of a novel virus now or in the future. What’s missing? Leaders and a populace with a deep understanding of a system. The effects stare at us daily, but what about the cause?

If you don’t understand how systems work, you focus on symptoms. You never dig into the root cause of the problem. You put out fires but never figure out how the fire started. Or better yet, how to prevent it in the first place.

Siloed efforts can work in tandem at home and abroad. The loss of valuable time and coordination of efforts slows down our collective response. We will find our way out of this calamity, but at what cost?

The word system doesn’t receive the credit it deserves. We use the term, but do we grasp the complexities inherent in any system?

The concepts of systems and systems thinking are not difficult. The structure applies to families, communities, and beyond. The main obstacle to systems thinking lies in our willingness to use it.

What’s in the Room?

“List everything you see in the room”

That began our study of systems. We listed things, many things, we saw in the university classroom.

First, we created individual lists that we saw. We shared our list of things. Some students identified minute details that many of us never noticed. We did not or could not see what they had seen.

Then, we began to categorize the disparate observations and look for relationships. We opened our eyes to view what we had seen from new perspectives.

The systems within the confines of that room and those that allowed us to be in the room took shape. We discovered systems that existed independent of us but still related to us.

As we looked deeper, we began to make connections. Without asking more questions, details blurred the systems of a single room.

The exercise illustrated our tendency to look first at “things.” This simple activity highlighted why we have difficulty “seeing” the world as a system.

That exercise taught me that we tend to look for immediate responses. Instead, we need to look for more than symptoms or things but at the system in place.

What Is a System?

Edwards Deming defines a system as:

“A network of interdependent components that work together to try to accomplish the aim of the system.”

How often do we function unaware of the interrelationship of our actions? When you change one thing in the system, what effect does it have on everything else?

For example, if you you choose to go on a trip, what are possible intended and unintended consequences?

We assume if an organization or a government exists then we have a system. Nothing could be further from reality in most cases. Three critical implications inherent in the definition of a system:

- A system must have an aim, a purpose.

- A system operates through an intentional focus on interrelationships and interdependence.

- The aim of the organization or whole has a higher priority than any of the parts.

Written statements of a vision, mission, or aim surround us. We see them online and in our organizations. The mission scrolls across the computer screen in my doctor’s examination room. Can we say we operate as a system because we have this physical evidence of an aim?

Let’s go back and look at the definition again. An aim without the network of interdependent components does not create a system.

Interdependent components that do not work together do not create a system. You cannot ignore the first two implications. Otherwise, fancy displays and rallies waste time and resources.

How do we change our thinking? What does it look like?

What Is Systems Thinking?

“Systems thinking is a discipline for seeing wholes. It is a framework for seeing interrelationships rather than things, for seeing patterns of change rather than static ‘snapshots’.” Peter Senge, The Fifth Discipline

Systems thinking uses the knowledge of the system to improve. This new thinking allows us to approach everything with a different lens. Donella Meadows makes this caveat:

“For those who stake their identity on the role of omniscient conqueror, the uncertainty exposed by systems thinking is hard to take.” –Donella Meadows, “Dancing with Systems”

What Can We Do?

We can do more, but we must take the first steps. Leaders, as systems thinkers, take an open and willing look at the issues at hand with new eyes.

With strength, they stand up against critics. Systems thinkers persist in ferreting out the root cause. They have a keen eye for seeing the whole and all the interdependencies.

A few basic expectations will prepare you for the journey toward systems thinking. Peter Senge outlines what he refers to as the laws of systems thinking – the Fifth Discipline. Senge offers 11 important laws, but three stand out as critical to our understanding.

“Dividing the elephant in half does not produce two small elephants.”

We cannot piecemeal systems thinking by looking at only one component at a time. To understand a system, we must examine all the interdependencies affecting the issue.

Most important, organizational divisions or functions must not stymie the analysis. We must remove barriers. And look across the boundaries that separate and isolate our work.

“Cause and effect are not closely related in time and space.”

The cause of the problem you face today did not begin today. What you see began long before the symptoms (effects) of the problem surfaced.

Think sleuth—investigate, dig, question. We assume the opposite of this law. Our starting point involves looking at the closest symptom or some person. Remember, we may not feel the pain (symptoms) for days, months, or even years from the initial cause.

“There is no blame.”

There is no one to blame. We created the beast, and we must assume responsibility for the beast.

Senge’s observation stands the test of time and experience.

“Systems thinking shows us that there is no outside: that you and the cause of your problems are part of a single system. The cure lies in your relationship with your ‘enemy’.”

How to Use Systems Thinking

Consider three steps to get started. Each step includes a few questions. They will help transform how you approach your work and life from a systems perspective.

Ask questions.

- How did we get to this issue?

- What happened prior?

- Has this occurred elsewhere?

- Do we know the underlying cause?

Identify the feedback loops.

- What are the key processes associated with this issue?

- What are the handoffs from one step or person to another?

- How are processes connecting, or not connecting across the work?

Recognize mental models.

- Do you understand how mental models affect decision making?

- How do you consider individual and group perspectives?

- What are the key assumptions individuals bring to the situation?

- Do you seek to understand or criticize and blame?

Strategies for Systems Thinking

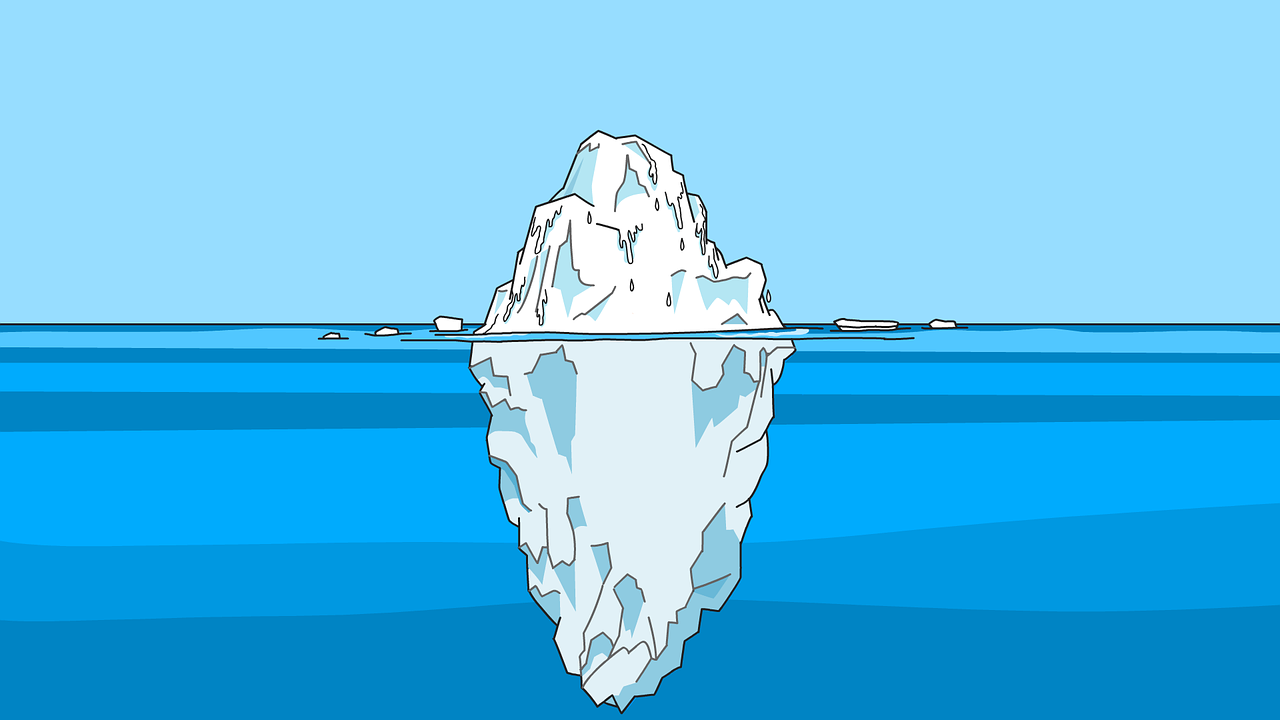

Peter Senge uses the metaphor of an iceberg to illustrate systems thinking. The visual helps us see how to leverage our knowledge of the system to affect change.

Peter Senge uses the metaphor of an iceberg to illustrate systems thinking. The visual helps us see how to leverage our knowledge of the system to affect change.

As you know, most of an iceberg lies below the surface of the water. Using the iceberg we will walk through a series of steps to analyze a critical event or even crisis.

Step 1: Events. At the surface, we see events. We observe what has happened and how we responded. What we can see is what we know.

Step 2: Patterns and Trends. If we begin to explore below the surface, we get a closer look at what has happened. This same event has occurred before, perhaps many times. Data in a simple run chart can provide a history of the behavior or results of the event.

Step 3: Systemic Structures. Push fruther down into the iceberg. Now we start serious exploration below the surface. These patterns of behavior reflect the system itself.

We have moved past a single event and begin to realize the forces that have contributed to the event. How has our system design contributed to or exacerbated the issue? Remember—cause and effect rarely occur close in space and time.

Step 4: Mental Models. Deep beneath the surface lurks our perceptions. These include our ways of thinking. Mental models hold the beliefs and values that people bring with them.

These collective perceptions, beliefs, and values have shaped the organization. How is our thinking or perceptions allowing the problem to form and persist?

How do you get to the bottom of the iceberg? One question at a time. Each layer uncovers isolated events. The questions we ask during our search help put all the puzzle pieces in place.

The leverage points that can affect deep change and improvement crystallize.

A Word of Warning

Explore the entire iceberg. Using a crash and grab for the quick and easy may lead you back to where you began. This time with the same or more serious problems.

What Can You Do Now?

Ask questions. Prod into the truth as best you can amid the noise. Learn more about how you can become a systems thinker.

For more information, I recommend exploring the Waters Center for Systems Thinking and a simple infographic, Habits of a Systems Thinker.

We need everyone thinking like a systems thinker!

Leave A Comment